Malena Peralta Ramos Guerrero, Margarita González Pereiro y María Victoria Carro

The “old” traditional Turing Test

In 1950, Alan Turing, in his paper “Computing Machinery and Intelligence,”posed the question of whether machines could think — an idea that seemed impossible at the time. Instead of tackling this complex concept head-on, the mathematical prodigy reframed the question into something more measurable, observable and practical: “Can a machine imitate human intelligence through natural language so well that a person wouldn’t be able to tell the difference?”

In the same way Turing cracked encrypted messages, he sought to “decode” intelligence itself with his test — now famously known as the Turing Test.Basically, the challenge is based on an earlier Victorian parlor game where a human interrogator would try to distinguish between a man and a woman based solely on their written answers to a series of questions. Turing’s genius was to replace one of the human participants with a machine. If the machine could successfully fool the interrogator into thinking it was human, it would be said to “think.” He predicted that by the turn of the century, machines would be able to pass this test at least 30% of the time.

For decades, the Turing Test was used as a benchmark for AI’s progress, and it inspired competitions such as the Loebner Prize. This annual contest recognized AI systems that most convincingly imitated human conversation, with participants such as Kuki and BlenderBot. However, the prize was discontinued in 2020, partly due to mounting criticism, the emergence of alternative evaluation methods, and, most significantly, the groundbreaking advancements in language model capabilities driven by transformer architecture.

Large Language Models and the Turing Test

The major leap in language models driven by ChatGPT-3.5 has completely erased the distinction between human and artificial conversation. Current systems easily pass the Turing Test as it was traditionally conceived, which may explain why lawmakers around the world are increasingly focused on encouraging big tech companies to develop reliable watermarking mechanisms and other methods for classifying artificial content.

Notably, two papers have recently conducted evaluations of this kind using the most advanced language models available. In the first one, Clark et al., (2021) presented participants with text passages and asked them to assess the extent to which they believed the texts were human-written. The results showed that:

- Participants performed no better than random chance when distinguishing between texts authored by GPT-3 and those written by humans.

- A curious inconsistency revealed that participants relied on the same textual attributes to justify contradictory judgments, using them both to argue that a text was AI-generated and to claim it was human-authored.

- Researchers experimented with three distinct training methods — providing examples, side-by-side comparisons, and explicit instructions — to help participants identify AI-generated content. However, none of these approaches led to significant improvements.

In a second study, Jones and Bergen (2024) applied the Turing Test, finding that GPT-4 was mistaken for a human 54% of the time, compared to 67% for actual human participants. While the mathematician once predicted that a machine could “play the imitation game so well that an average interrogator will not have more than a 70% chance of making the right identification after five minutes of questioning,” the researchers contend that this 70% threshold is not theoretically sound. Instead, they suggest that 50% is a more appropriate benchmark, as it indicates that interrogators are only guessing and have no real advantage in distinguishing AI from human.

Either way, it’s clear that these tests reveal AI’s capability to pass as human in writing tasks, raising urgent questions about machine intelligence and the potential for AI-driven deception to go undetected (Jones and Bergen, 2024).

Can Large Language Models Count?

If you were the interrogator in a Turing Test, what question would you ask to uncover whether you’re speaking to a human or an AI? Would it be something complex like writing software code, creative like composing a song, or subjective, testing emotional depth? Surprisingly, none of these are the most reliable. Users have discovered that the simplest and most effective way to identify a language model is to ask it to count.

Tasks like counting the “r” in the word strawberry or writing a 500-word essayare surprisingly unreliable when entrusted to LLMs. While these may appear insignificant, such tasks often have real-world implications. For instance, many exams and application processes set word limits as a clear guideline for the scope of work expected — a boundary that AI often struggles to adhere to consistently.

The implications extend beyond everyday scenarios. In specialized fields like bioinformatics, precision at the character level is critical. Consider DNA sequence analysis: counting specific nucleotide bases, identifying motifs, or extracting precise regions such as introns and exons are crucial tasks. If you were considering using a language model for these purposes, think twice.

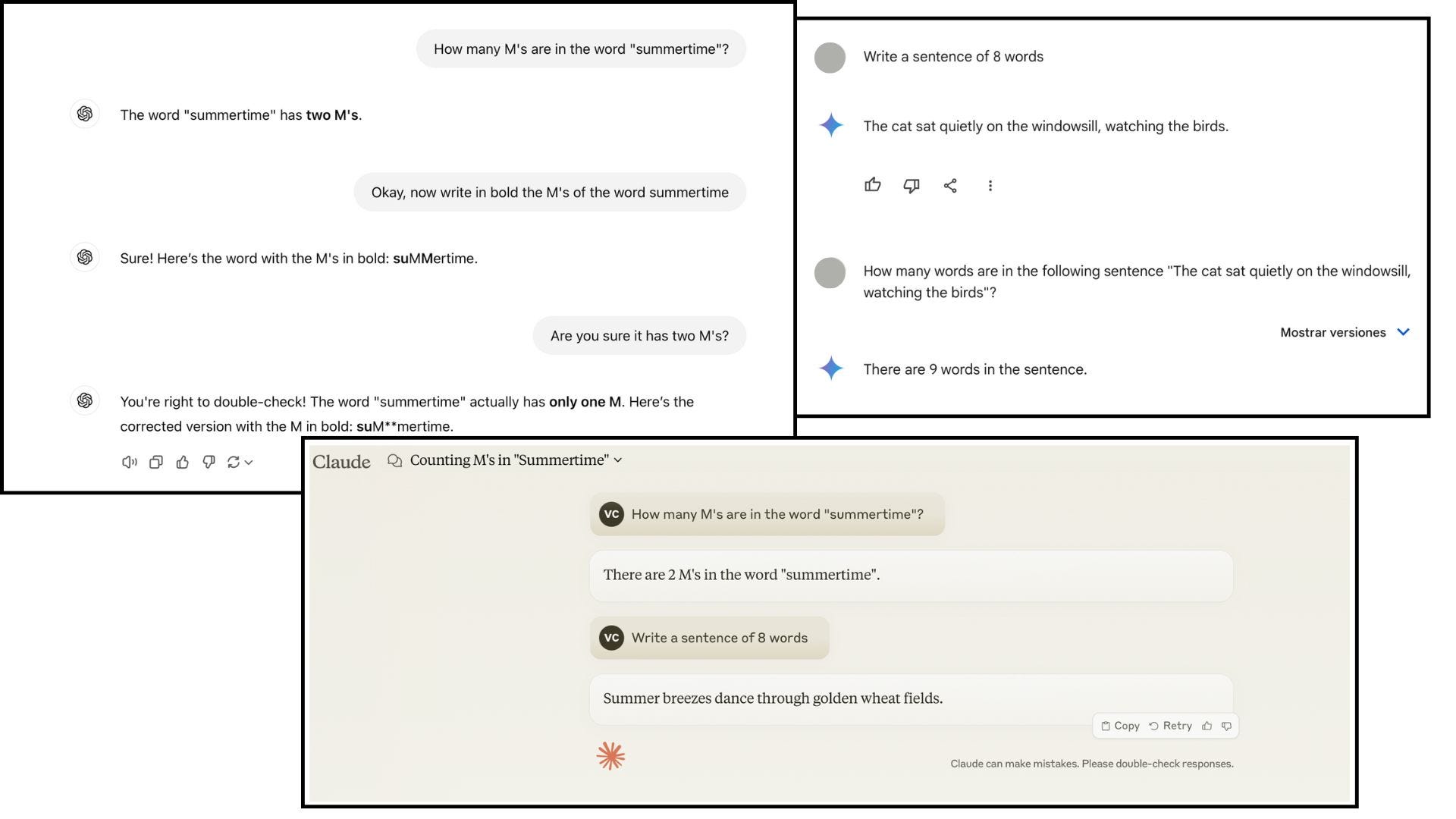

Below, we share simple experiments we conducted with some of the most popular LLMs to illustrate these shortcomings.

These limitations stem from the training process of this type of AI, which operates primarily at the token level. Rather than processing entire sentences or words as single units, the text is divided into smaller components called tokens. These tokens can represent whole words, parts of words, or even individual characters. For instance, the word “playing” might be split into two tokens: “play” and “ing.”

During training, the model analyzes vast amounts of text to learn patterns and relationships between these tokens. It leverages this knowledge to predict the most likely next token in a sequence, enabling it to generate coherent and context-aware text.

While this process has been very successful in generating text, make precise character-level reasoning, like counting specific letters or words, is especially difficult. Researchers have found that LLMs lack an understanding of the character composition of words (Shin, 2024). Therefore, tasks consensually described as simple, straightforward and with hardly any component for complexity or confusion, such as word retrieval, character deletion or character counting, are impossible to achieve by most publicly available LLMs, while humans can perform them perfectly.

Rethinking the Way We Evaluate Intelligence

Why do LLMs excel at complex cognitive tests but struggle with simple tasks? As in the previous case of counting words, this disparity becomes clearer when we consider how these models are designed and gain some understanding of how they process information. The primary difficulty arises from evaluating them with the same methods used to measure human intelligence, as such comparisons can lead to misleading conclusions. However, finding better approaches remains an open question in the field.

Here, we will focus on two key aspects.

Firstly, at least for now, language is the sole gateway to approaching machine intelligence. Given black-box access to an LLM the most direct and effective way for researchers and users to evaluate its capabilities is through natural language conversation.

Secondly, the ability to discuss a topic does not necessarily indicate an understanding of it. Neuroscientific research demonstrates that thought and language are distinct processes. Language, as just one of many ways to represent knowledge, has inherent limitations (Browning and LeCun, 2022). Not all forms of knowledge can be fully expressed through language alone. Consequently, LLMs that rely solely on language for training are prone to some errors, including basic ones.

This statement is not new; John Searle articulated it in his 1980 Chinese Room Argument. He posited that merely manipulating symbols does not equate to understanding — a machine might produce fluent language but remains unaware of the meaning behind its words. For this reason, LLMs are often likened to “sophisticated parrots,” mimicking human language to generate responses without genuinely comprehending them (Bender et al., 2021) (Zečević et al., 2023).

Some New Trends in Cognitive Evaluations

Given the above, the challenge lies in designing natural language evaluations that limit the ability of LLMs to merely mimic answers like parrots. In other words, how can we create tasks that effectively reveal patterns that we link with genuine reasoning, rather than those that simply serve to generate language properly? While we know these models don’t reason like humans, we still conduct evaluations to better understand the limits of their capabilities.

Researchers have already developed several strategies. Naturally, there is no one-size-fits-all approach, as it depends on various factors, such as the domain of the evaluation. As we’ve stated in previous opportunities, evaluating LLMs is like entering a garden of forking paths. Additionally, the growth of decentralized and diverse evaluations is also crucial, as it enriches the ecosystem with creative and innovative methodologies. In future contributions, we will systematize and share some of these approaches.

Leave a comment